Cartoonist David B. is ‘an exceptionally gifted artist who…reveals hidden truths inexpressible in another medium’. Quite a claim – but what think you?

In earlier installments of these BD reviews I have tended to focus on psychedelic science fiction, the bizarre, or indeed the barely coherent. I like that type of stuff, since I prefer comics that remain rooted in the disreputable origins of the medium while going much farther creatively. By contrast most of the “graphic novels” that get reviewed in the Guardian bore me: far too polite, lacking in violence and bad taste, cravenly begging to be allowed to sit at the master’s table alongside Ian McEwan novels. Yawn.

However it’s not all lunacy all the time round my house, and today I am highlighting an exceptionally gifted artist who even the most words + pictures resistant Dabblers might enjoy.

One of the most sophisticated cartoonists in the world today is David B., a Frenchman little known on these shores, although his protege Marjane Satrapi scored a huge success with Persepolis, the graphic novel and later animated movie about her childhood and adolescence in Iran. That’s a great book and well worth reading, but all the same her storytelling is exceedingly straightforward. Something happened; she draws it. The result is a book that’s funny and sad and immediately accessible to outsiders.

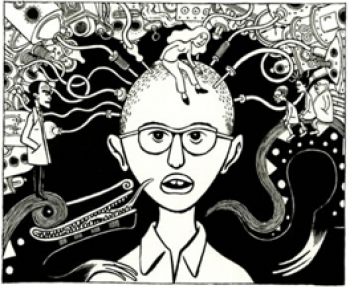

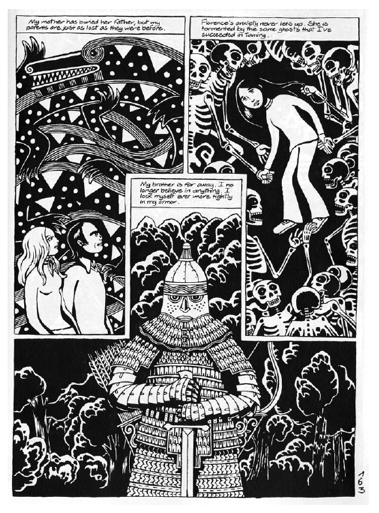

Although it’s clear that Satrapi learned stylistically from David B.’s art, his approach is a little different. Something happened; he draws something else; but on a deeper level this apparently fantastical digression will reveal hidden truths inexpressible in another medium. This approach is rampant in his masterpiece Epileptic, which did see a release from major publishers in both the UK and US even if hardly anybody bought it. On the surface it sounds rather unappealing, a dreary piece of sick lit, and- horror of horrors- even a little worthy. It’s a memoir of David B.’s life growing up with an epileptic brother and the various cures his parents sought for their afflicted son, you see. But look at the sequence below:

As these few panels make clear Epileptic is much more than a diaristic retelling of things that happened, rather David B. probes deep into the disintegration of his brother’s personality, the fantastical hopes and delusions of his parents and the growth of his own imagination, and as often as not illustrates this expressionistically via images of demons, huge battles, dreams and so on. We are not talking about an undisciplined, messy surrealism here; rather there is a strong sense of design and order within which these wild imaginings exist as dream-demons cohabit with gurus offering macrobiotic cures. David B’s approach is unique, and it’s actually very difficult to sit down and analyze what he is doing on each page, and even if I could I wouldn’t want to. But there is logic to the strange alchemy by which he interprets and reinterprets the world, even if the reader can only dimly intuit the outlines of it. But who needs more art that’s obvious and lays itself open? There’s enough of it already.

Epileptic is generally seen as David B.’s greatest work, and it may well be. However he is a prolific cartoonist and in the last year or so the British publisher SelfMadeHero has brought out two of his more recent books. The first of these,Black Paths, is a fine example of another side to his oeuvre – stories set in obscure periods of history when bizarre ideas momentarily flourished and entered the mainstream. In this instance David B. focuses on the brief period after World War I when the Italian poet Gabriele D’Anunzio presided over the city of Fiume, drinking out of a human skull, consulting with the insane and coming up with utopian schemes for the salvation of Italy, the world, and whatever else flew into his brain for a few seconds.

WWI veterans fought in the streets, gangsters and crooks and Dadaists cooked up plots while D’Anunzio declaimed poetry from the balcony of his palace. David B’s hero Lauriano writes, fights, steals, falls in love and is haunted by the ghost of a friend who died the in war. The fantastical reality D’Anunzio created is well served by B’s unique ability to unveil the continuity between reality and dream.

In Black Pathshowever David B. sticks fairly close to the known facts of the era, whereas in another historical work The Armed Garden he takes real individuals from the millenarian Taborite army of Bohemia and launches from that point into a lyrical surrealism. Some reviewers complained that Black Paths is short on plot, but this is rather to miss the point. It’s a chaotic sequence of adventures and events that evoke the anarchic, destructive creativity of D’Anunzio’s dream kingdom. It’s funny, poignant and beautifully drawn and well worth anyone’s time.

Recently meanwhile SFH published another David B. volume, a collaboration between himself and an expert on the Middle East called Best of Enemies. Billed as a history of US and Middle East relations it demonstrates how successfully comics can be used as a medium to condense a difficult non-fiction topic into an easily digestible précis. Do I have enough time to read an actual book on this admittedly important theme? No. Will I read a 120 page summary if it’s illustrated by a master cartoonist? Yes.

Of course, as with everything, the success or failure of such a project depends on the skill of the creators. As it is, the book is very nearly derailed at the beginning by a few cringe-inducing jabs at the War on Terror. Swiftly however the book gets stuck into its main subject matter, from America’s first encounter with Barbary pirates right up until the Mossadegh malarkey in the 1950s. The prose is succinct and factual, but it offers more than just a sweeping survey. There are fascinating little details, from accounts of American vacillation between paying off Arabs and fighting them to Saudis requesting access to porn on US battleships in the 1950s.

For sure I learned a lot from this book, but it’s David B.’s illustrations that make it work so well. Via his eye, American sailors and Barbary pirates face each other across the seas like aliens, huge turbans bristle with limbs and swords and guns, Iranian agents open their maws to guzzle money. There is a wonderful page layout on page 71 as heads sprout out of oil pipes that snake across the page, until at the bottom an open spigot pours black oil into the open mouth of a grinning Roosevelt. By contrast David B. illustrates faithfully scenes that actually happened –a meeting between the Shah and a US general that began with the Shah silently climbing on a table for instance. The direct, unadorned truth is also inherently fantastical. It’s a great book and I look forward to volume II.

The general upshot of this review then is that David B. is a great artist and everyone reading this should rush out and buy his books to persuade English language publishers to translate more of his work.